Patience is not a virtue I was blessed with. No-patience can be advantageous when one needs to head for the wall like a wrecking ball, and the inability to quietly wait did me some good as a young artist living alone in New York City, but it no longer serves me as a wife or mother.

That I do not outsource the care of my child (hopefully children!) and that I try earnestly not to be a self-centered narcissist around my husband is of the highest importance to me. The first three years of my child’s life are so unbelievably fleeting and sacred that I PERSONALLY cannot bear to miss a minute of it, and thank God I don’t have to. This, then, means that I no longer spend my entire day locked in my studio smoking pot and etching copper plates in ferric acid or working with lead tin yellow oil paint or reading Dostoevsky novels to myself alone on the porch, as that would amount to child abuse. Out of practical necessity I have had to modify (what art students refer to as) my “studio practice,” leaving the large workspace upstairs mostly abandoned, and bringing my work down to the first story.

I’ve thankfully never struggled with what I perceive as the false Mother-Artist dichotomy. To me, living is an art: from the clothes one chooses to the food one eats, and even the totally wild art of child-rearing. As Louise Bourgeois said, “Art is not about art, it’s about life, and that sums it up.” I do not make art about art, and find most complaints about children eating up pre-mother art time distasteful. I think if you care that much about the art you will find a way to make it. Becoming a mother has completely shattered all my preconceived notions about what it means to be a “real” artist in the world. I just don’t care anymore. Childbirth literally smashed any illusion of ego I had into a bloody, milk-pulp.

Maybe if my husband and I meet a wonderful little Greek yiayia in NY at church who wants to spend a few hours with my daughter every week, I will have more time to work on egg tempera paintings while they both bake koulourakia together. Until then, though, I’ve gotten more resourceful with what art I choose to employ while spending the day with a toddling child. Enter one of the most primordial art forms for busy mothers: WEAVING.

I promise to spare the reader from tired, didactic art-historical pontifications regarding the so-called devaluation of weaving as “women’s work” and therefore not “Art.” The history of grievance carries weight but it totally folds against the crushing forces of “late capitalism.” Anything can and is now sold for stupid amounts of money in galleries, including weavings by women and they/thems. What appeals to me more than making a feminist art statement is the practicality and tactile nature of working with yarn, including the psychedelic qualities of colors and the promise of natural dyes that weavers have always employed. Even Van Gogh relied on a red-lacquer box of bright yarns to complete his color studies before painting.

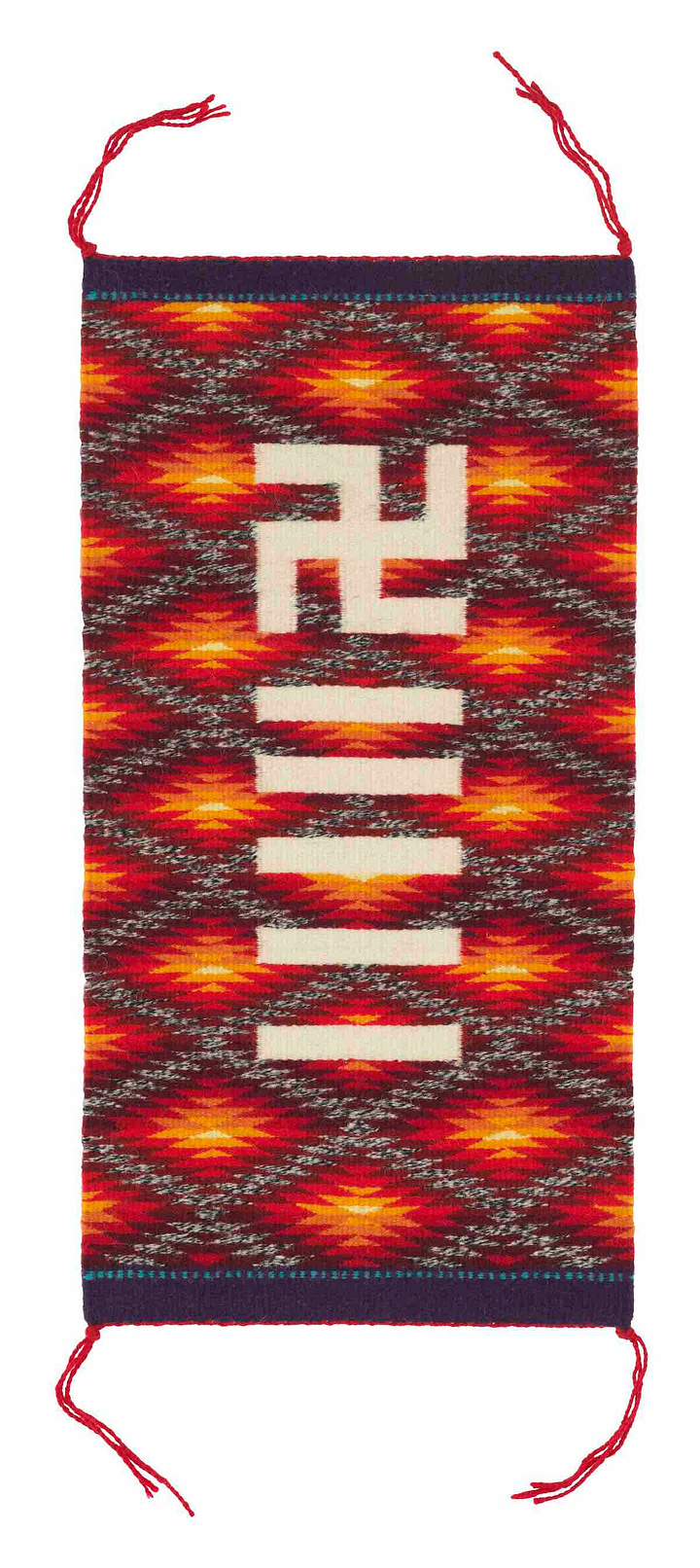

I think the most beautiful, weep-worthy gallery show I ever saw was a 2018 exhibition at Pace NY of Agnes Martin paintings hung with stunning Navajo weavings, which included Diné First Phase Chief blankets. Agnes’s stripes radiate with the same mystical beauty and meditative patience as the traditional Navajo “women’s work." (Aren’t Martin’s paintings also necessarily “women’s work” since a woman made it ??). I don’t think the blankets were sold off but the fact that they were hung as “Art art” with Agnes’s million-dollar paintings says a lot. We are no longer living in an era where Anni Albers took weaving classes at the Bauhaus school because it was the only option for women at the time (but thank God she did).

My husband built me a decently sized Navajo-style standing loom while I was pregnant in the spring of 2023. Navajo/Diné looms and the weavings traditionally made on them glow with the utmost earthly elegance and transcendence. Navajo iconography, from First Phase stripes to the Spider Woman Crosses and whirling logs (not swastikas) cuts right to the primordial spiritual energy of North America like hardly anything else can. The hand-spun wool yarn, the golden Rabbitbrush it was dyed with, and the wood of the loom literally embody the western landscape. And despite their relatively simple composition when compared with many modern looms, the possibilities for tapestry on a Navajo loom are incredibly vast. Just look at the work of Melissa Cody and Marlowe Katoney.

Because I did not have access to a Navajo weaving class, nor did I ever have any plans to feign making “Navajo weavings,” as a white, fourth-generation Montanan it took me two months to learn to warp it correctly and another three to figure out how to open the sheds properly.1 I am only now, two years later, more than halfway through the first weaving I started, and this is only because it’s Lent and my time for weaving has also been the hour to send up intense prayers to God to make me less slothful, stupid, and prideful. I’m also moving in two weeks and have no choice but to finish.

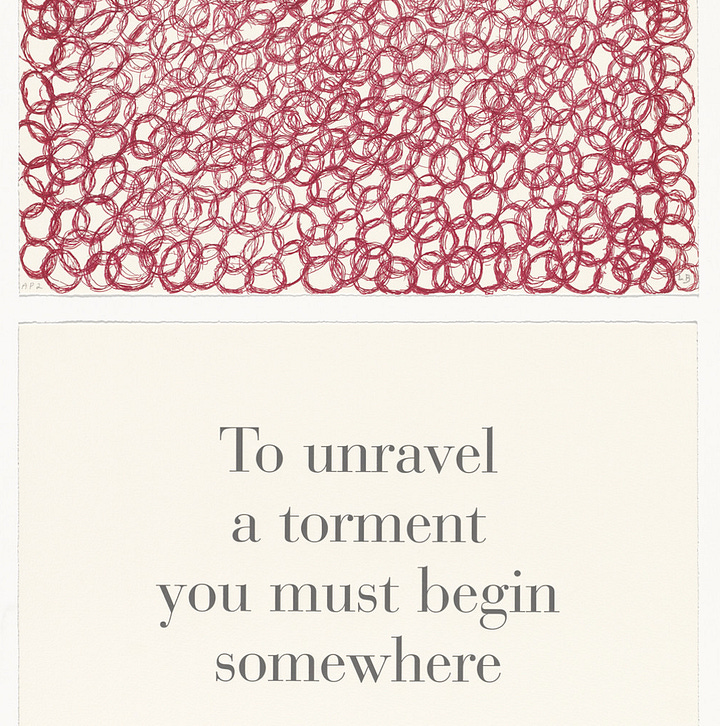

The focus and patience required to learn the deceptively simple task of tapestry weaving, open-faced with the weft (horizontal thread) covering the warps (vertical lines) like thousands of primordial crosses, was grueling. I am impatient, demanding, and overly reactive to difficult and/or repetitive / fussy tasks. I’ve given up learning ceramics and proper oil painting technique at least three times, and to this day I can only knit rectangles and tubes, but I’m moved by a desire to make pictorial weavings and an obsession with the way to non-academic abstraction. It sounds melodramatic and canned, but the only thing that keeps me weaving are the countless prayers to keep going. Now I see warps and wefts in my dreams.

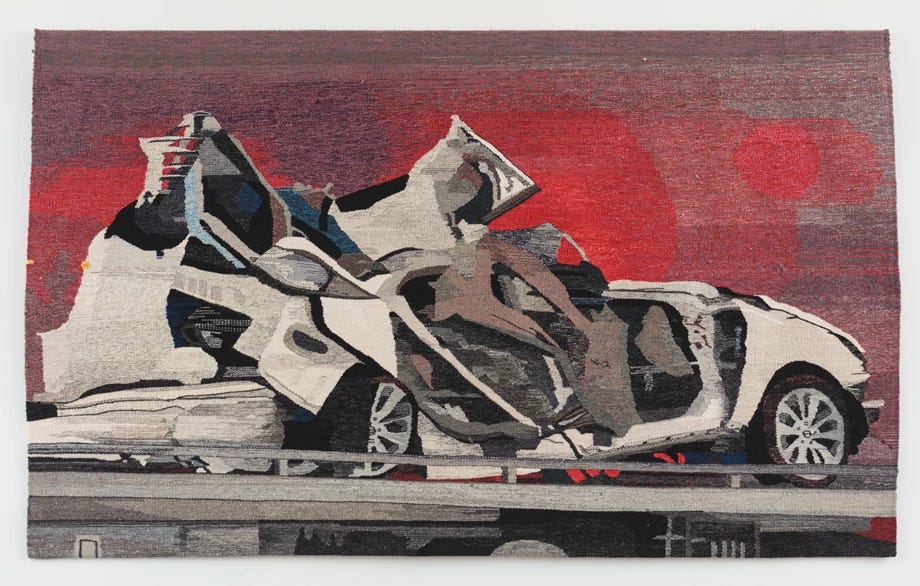

It’s exactly like running very hard while sitting totally still. If you work through pain with the Penelope-level patience to be a good wife and weaver, you will develop the spiritual endurance to keep going— and the image will reveal itself to you, no matter how imperfect. The contemporary weaver who is NOT a wife (I like her car crash tapestries) Erin M. Riley says it perfectly: “Every day, I tell myself, ‘This is too hard. This is impossible,’ and then I figure it out… For me, weaving is a lot of wins. I force myself to do something, and it’s always worth it.”

What began a month ago as a devotional prayer to be a better artist-mother and to stay the hell away from my phone all at once quickly became the voice of one crying aloud in the wilderness. Right before my husband left for a work trip to Copenhagen, I came down with a flu and bronchitis that was so bad it gave my close friend (a young athlete!) PNEUMONIA. I have never prayed harder in my entire life that my spouse and the baby would be spared from sickness, and those prayers were answered. (I will write about the gift of illness in-depth next time). Still, I had to care for my toddler alone for nine days while hacking up green sputum with zero appetite or energy. The only activity that kept me grounded to this planet while my husband was gone and our daughter was napping or playing with her books or piano was weaving. I prayed ceaselessly for the presence to complete the tasks ahead of me: caring for my daughter, beating down the weft, keeping the house clean, and waiting patiently for my husband (yes, like Penelope).

When the bitter, mountain prairie wind finally stopped blowing after countless days, I pulled the loom out onto my porch and wove for a blessèd three hours in the sun, listening to the Grateful Dead while the baby napped. My current tapestry design began as a meditation on the five wounds of Christ, but has since taken on a life of its own and morphed into a landscape of mandorlas, crosses, and celestial orbs flying over the earth. It is a humble weaving littered with lice (visible warps) and poor tension, and any self-respecting Navajo granny weaver would laugh HARD at it, but it is True.

I am grateful for the squandered time that prayer at the loom has helped me regain, remembering Eliot’s call in “Ash Wednesday” to “Redeem the time/ Redeem The unread vision in the higher dream.” The small hours spent learning this indigenous tapestry of the earth have gifted me with enough patience to endure two horrific respiratory illnesses stacked on top of each other, the maternal repetitions that will present as tedium or ennui if one forgets they will be dead soon, and the spiritual scourge of impatience itself.

This morning my dear friend and patron Richard Nelson called and asked what art supplies I would haul to NY in two weeks. I said I’d leave the little printing press and hot-plate he loaned me, but to my husband’s horror I wanted to bring my new flat file cabinet, two tubs of oil paints, three easels, 32 pigment jars, drafting tables, a rolling cart with glass palette taped to it, watercolors, gouache, pastels, reams of paper, copper plates and etching materials, etc. After sending a photo of my weaving (almost finished) he responded: “I would consider doing what women have done for generations and just bring the minimal things that you need to make beautiful art. It is the males that load up moving vans and spend the whole lives getting up studios without making anything. think of the beauty we would have if you made one tapestry a month and then had a show of your 12 months. no need for flat files, presses, easels, canvases. just you and your yarn.”

(a huge thank you to my inspiring weaver friend Nico Larsen for all her patient guidance and encouragement).

Any tips for someone who feels called to weaving and has absolutely no idea where to start? My natural inclination is to go buy a bunch of sheep, but that seems a bit premature!

Gosh I love your writing, Birdie! I'm not an artist but the idea of weaving has been similarly tugging at me for years and years. I was blessed to be freely gifted a 95cm table loom last month with a whole boot-load of naturally dyed, hand-spun rug yarn. After days of fixing up the loom, re-tying the shaft chords, cutting and sanding back odd bits of dowel for holes that had lost their plugs, I've finally warped and started a small rug. For me the actual practice of weaving (perhaps bar the preliminary warping) tends to feel appealing and suitable at times when other kinds of work feels impossible. I've been chipping away at the rug with my daughter afoot, even on days where I've felt like I could otherwise be in bed.... Tapestry & Navajo weaving is calling to me too but I want to get the hang of this salvage-to-salvage single-pass weaving business first, then we'll see...